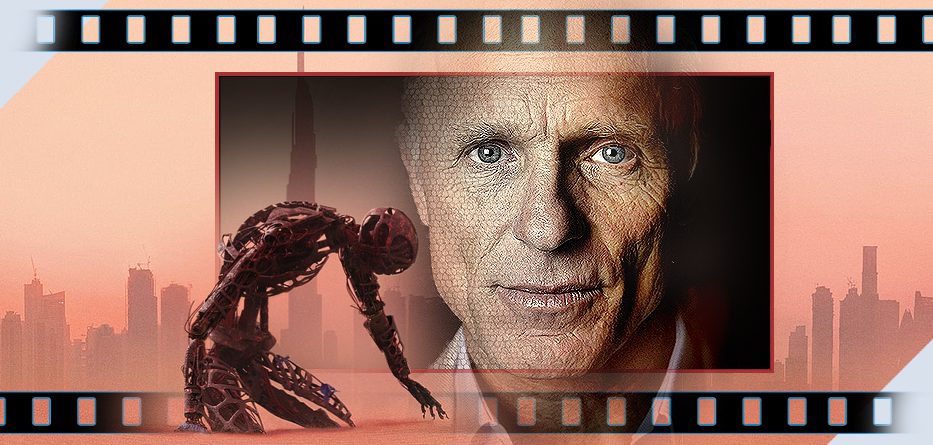

Once upon a time William entered the landscape of Westworld and it changed his life. Seeing himself as neither hero or villain he orchestrated a take-over of the company that built it, but over the years, that choice and its consequences has cost him dear – in both his business and personal life. After the loss of his daughter, whom he killed, thinking she was a ‘Host’, he’s not been able to clearly distinguish between reality and the synthetic world of the parks – he’s even doubted his own identity, wondering if he too was a Host. if so, would that absolve him of his sins?

Now he’s visited by Charlotte Hale who sends his company is on the brink of being bought out, once and for all and only he can stop it – but is he ready to re-enter the world and who would want t stop him?

Elsewhere Bernard and Stubbs believe they have discovered Dolores’ plan and aim to stop it and Maeve tries to find clues as to Dolores whereabouts and immediate intentions.

However, they are all about to find out just who or what Dolores smuggled out of the parks – and just how far she will go…

*Spoilers*

At the best of times it’s always been hard to work out the identities of the people we’re watching on Westworld – either because of the interconnected or disconnected timelines or because the Hosts aren’t always obvious. It’s become even more complex with the fact that even within the synthetic community, the Host ‘bodies’ don’t always match the personas inside (for example, Dolores escaped Westworld last season while in the artificial Charlotte Hale’s body). One of the big mysteries of this season were which Host personalities Dolores managed to liberate during her escape. One of the big ‘moments’ of this episode was the seeming revelation that many of the Hosts in the real-world now appear to be aspects of Dolores. At least, maybe. It certainly seems that way…there’s the obvious, prime Dolores model we’re following, but she seems to be within security controller Connells (Tommy Flanagan) during her encounter with Jeffrey Wright’s Bernard (who seems to be able to switch between two personalities but neither of them Delores), within a real-world version of the warlord (now Yakuza boss) Maeve met in ‘Shogun-World Musashi/Sato, played by Hiroyuki Sanada and within Charlotte Hale as she confronts the Man in Black in an apparent attempt to raise him from his nervous breakdown.

Westworld is fascinating, beautiful and complex. But despite swords, guns, fights, flying cars and robots – and a budget to render them exquisitely… does it actually make you care?

Except. If it’s as simple/complex as that, then there’s more questions and disconnects. Any doubts that ‘Charlotte’ had about her inner-meaning (in Tessa Thompson’s tour-de-force last week) suddenly seem illogical or negated and the differences between the actions of the various other Hosts to date become questionable. It all feels like we’re heading towards a denouement where the showrunners will sit down and have to explain certain things rather an the show doing so – and that’s a continuing problem.

It’s telling that the Dolores (Doloreses?) aspect of the story overshadows another massive development that would normally have been a dominant plot-point: the apparent flashback to Paris being reduced to a radioactive wasteland – a mushroom cloud and people in hasmat suits roaming through the countryside. It looks to be further explored next week, but it creates some more distant from this being ‘our’ world. We know, vaguely and from on-screen graphic etc, that Westworld‘s main events are supposed to be about thirty years in the future but the sheer leap in tech, the destruction of Paris and the fact that there seem to be wide-open fields within sight of the French capital make this feel ever more ‘alternate’ rather than futuristic – another unfortunate disconnect.

In the recent Picard finale, the finest point of a troubled climax was Data saying that to fully understand the human experience it has to be finite and he had to ‘die’. The problem with the current Westworld set-up is that it’s going the opposite way – or the same way very slowly. While it’s accompanied by some decent fight choreography with sword and gun, Maeve’s somewhat unexpected ‘demise’ no longer has any of the finality that’s needed to give the scene the real emotional impact it needs. Like a comic-book, it’s the ‘They’re dead – hmmmm, when will they get better?‘ feeling that what we’re experiencing is a comma rather than a full-stop. It’s clear we haven’t seen the last of Newton/Maeve, so while the show defaults to yet another great visual (a mixing of blood and milk around Maeve’s ‘body’) it’s somewhat style over content – a tightrope the show continues to indulge, sometimes to its detriment.

Ed Harris is a great actor and always interesting to watch, but four episodes in I was struggling to remember where we’d left the ‘Man in Black’ previously. His scenes with the ‘ghost’ of dead daughter Grace (Katja Herbers, more recently seen starring in Evil) – whom he mistakenly took for a Host in Season two and subsequently shot – produce strong moments but feel more like a footnote – what did they accomplish but to remind us of a plot-thread we’d probably forgotten about in the midst of newer turmoil? If it’s to answer the spoken question about which is best: to be a Host with pre-programmed actions you aren’t responsible for, or a real human who’s committed a heinous act of his own choosing… then the question isn’t really answered and we exit, stage-right with the now asylum-committed William simply asking himself the same question as he did in the first scene.

Adding on to the visuals we saw in the first episode of the new run, there’s an ever-more Blade Runner feel to the downtown city and its neon-hued eastern influences and the glimpse of the ‘Eyes Wide Shut‘-like party inhabits a different zip-code in the same world – the idea that decadence is just a matter of degree and taste. While that might work into the ‘hard won’ loyalty/disdain that Serac (Vincent Cassel) has for mankind in general – certainly the feeling that it’s destroying itself form within – it also feels a little at odds with the control factor of every human being the victim of a computer-system that designates their fate (a BIG sf idea that doesn’t feel like it’s getting equal time on a show that’s already overly-ambitious).

You’re left watching The Mother of Exiles with the mother of all head-scratches – the feeling that the extraordinary production values of the show are more important than its story – that, like a psychologist’s couch, the theological debate, however pretty, never amounts to more than ‘but what do YOU think?‘ answer; that the scenery outside the window is just expensive decoration and that however beautiful and graceful aspects undeniably are, there’s more of the clinical fascination at work than organic passion – a problem that Jonathan’s brother Christopher encountered when the lucid-dreaming-themed Inception became simply an ode to sharp-edged, pixel-painting virtual reality rather than feelings).

Westworld is fascinating, beautiful and complex. But despite swords, guns, fights, flying cars and robots – and a budget to render them exquisitely… does it actually make you care? That’s the fundamental question and, once again, perhaps the show’s fundamental irony and self-same obstacle. It’s too busy being clever to make you passionate.

- Story8

- Acting9

- Direction9

- Production Design10