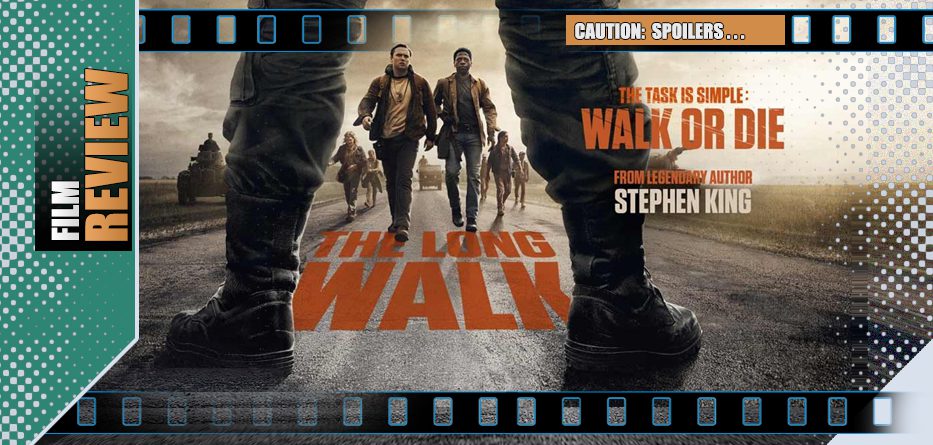

In an alternate history, with America emerging from a modern civil war, a special event allows one lucky citizen to win anything they want. A lottery selects fifty people, supposedly at random, to take part in a ‘walk’ from which there can be only one winner. The catch? All participants have to continuously walk, without stopping for food or sleep or ‘waste-disposal’ and anyone who tries to leave or falls beneath the 3.5mph speed limit will be shot by the troops that guard them.

People have different reasons for taking part, different tactics for surviving and different dreams of what their ‘wish’ will be.

But as the hours turn into days and contestants literally fall by the wayside, is there any time or point in making friends? Who can possibly win and what will be the cost?

*spoilers*

The Long Walk defies the usual structure of many a feature film. Like the unrelenting road itself, there’s a solid throughline with very few chances for detour or dalliance and though the backgrounds change as the story progresses, the camera frames a singular procession and mission statement: we’re not here as a part of some travelogue or day-trip through the countryside, we’re watching a gradually diminishing group of desperate people traipsing along a road, likely to their death. There is punctuation along the way, sometimes bloody, sometimes sudden, but the question is the same throughout, from the first frame to the final: who will be the last man standing?

The concept itself demands two deceptively tricky things to succeed – the cast of characters have to keep us invested in their fate and the camerawork has to be more than simply pointing its lens and hoping for the best. Thankfully, The Long Walk achieves both: though it doesn’t push as many boundaries as it could, it delivers a consistent and growing sense of dread, making even widescreen shots seem dangerously claustrophobic.

Stephen King released the original novella in 1978 – during his time using the pen-name Richard Bachman – and has spoken that he wrote the story when in college and there was an all-too-real fear amongst young men of being drafted to fight in Vietnam. In that sense the subtext definitely becomes the text. The printed tale is tense and unforgiving and though there are tweaks to the narrative (on screen it’s 50 participants rather than 100, the lowest speed they can walk is 5 mph in the novel and now 3.5mph on the screen and central character Ray Garraty is a little younger on the printed page), the changes appear practical ones and the intent remains the same.

By its very nature of its men-only participants (the film never addresses the gender factor), The Long Walk is a testosterone-filled story, but more the sense of enforced fraternal camaraderie of prison dramas (such as The Shawshank Redemption) rather than the grunting, sweating, bullets-and-chrome variety of, say, Zack Snyder.

Pragmatically, not all fifty participants get equal time and even those that get named don’t always last long, but, generally, the main ‘walkers’ themselves all offer solid performances. Cooper Hoffman (son of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman) continues to make his own mark as Walker #47/Garraty. He makes the character sympathetic yet driven, making him the person you hope wins while fearing he won’t. Walker #23 Peter McVries (Alien: Romulus‘ Andy) plays David Jonsson, a realist who befriends Ray as they support each other along the way, yet knowing that they can’t both survive. We also meet Garrett Wareing as the solemn #338/Stebbins, Charlie Plummer as the troubled, abrasive #5/Gary Barkovitch, Karate Kid: Legends‘ Ben Wang as the chatty but wholly unprepared #346/Hank Olson and Joshua Odjick (also on show in another King entry IT: Welcome to Derry) as the proud Native American #48/Collie Parker.

Ultimately, The Long Walk achieves the feat of being solid, knowing adaptation of a Bachman/King novella (in and of itself, no mean achievement), but misses out on greatness for exactly the same reason. In making the decision to strip the adaptation back to basics, director Francis Lawrence (Red Sparrow, The Hunger Games: Catching Fire/Mockingjay) does a good job of making us care without a ton of bells and whistles on which inferior feature films often rely, but simultaneously side-steps the opportunity to expand the ideas and push the frame with any real world-building. We get glimpses and mentions of the regime that’s created the nihilistic journey to entertain the masses but no real sense of its particulars (perhaps think a slimmed-down The Hunger Games without any of the garish prêt-à-porter or over-the-top obstacles). There’s the idea that the walk is more fixed crowd-control than a lottery, but that public perception is reduced to seeing a few weeping family members (including Judy Greer) wave goodbye and then the thin, strangely apathetic voyeurs who litter the route like wraiths and show little emotion either way. You’d expect such an undertaking to be of interest to the baying masses, (a la The Running Man remake from yet another King novel), but it’s so self-contained, that we rarely see beyond the immediate tarmac and roadkill. That’s a perfectly fair artistic choice, concentrating on the main characters and echoing the text – and it works better on some occasions – but it would have been interesting and informative to understand the wider peril and parameters rather than stick with a sprinkling of backstories from a small group of characters (most of whom, we understand from the start, won’t survive).

For example, Mark Hammil, cast against type, is the unforgiving military commander watching over the shuffling mass from the back of a jeep, alternatively yelling toxic encouragement and sterile recriminations. One of the few disappointments is in how little he’s used. Initially introduced with a self-serving speech about effort and survival, you expect him to be the malevolent boogeyman hanging over the entire venture, but for the most part the threat comes from interchangeable soldiers merely fulfilling the rules of killing anyone who deviates from the path or can’t keep up to the set pace. Hammil enjoys chewing the scenery and we get a few drops of why he’s generally loathsome but it would have given the film a sharper edge if we didn’t have to dislike him from afar. If you want to keep the oppressive state faceless, you leave it to the imagination and inferences along the way, but if you cast Mark Hammil – or for that matter the versatile Judy Greer – you’re asking the audience to believe there’s something important in that portrayal. In this case, Hammil’s character doesn’t even get a name beyond ‘the Major’.

If the original novel was brutal, the screen version of The Long Walk is both angry and resolved but isn’t so nihilistic as to turn off its audience nor so sweet as to squander the subject-matter. It has a running (walking?) time of just under two hours which feels like good pacing and it walks the line between moments of nihilistic carnage and a celebration of the human spirit. It might not have the historical staying-power of some of King’s signature best known work, but its strong cast make it a worthwhile entry.

- Story8

- Acting10

- Direction9

- Production Design / FX8