[Warning. Spoilers for Season 4…]

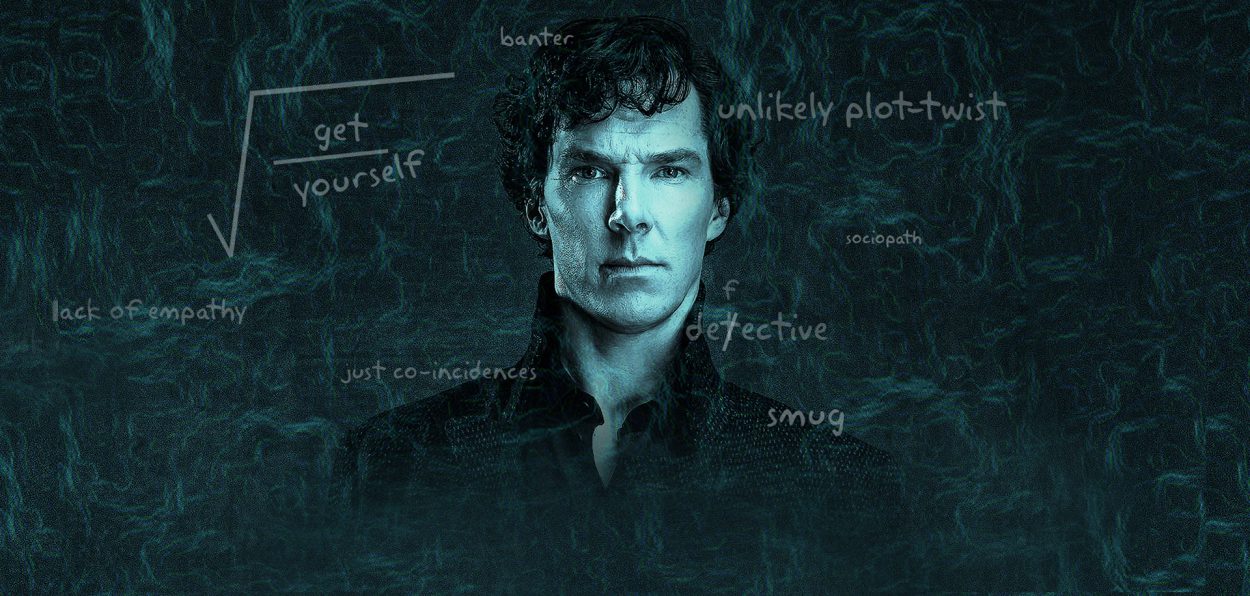

There is no doubt that as far as cult successes go, Sherlock (shown on BBC1 in the UK and Masterpiece/PBS in the US) is as high-profile as you’re likely to get. Unlike traditional American shows that run to either thirteen or twenty-two episodes a year – and can be crippled by audiences deserting them over a long hiatus – the BBC-produced series seems to revel in going AWOL and then giving less than a month of drive-by stories before vanishing in a puff of enigmatic and dodgy-aroma’d pipe-smoke once more. Despite the chasm between ‘seasons’, viewers flock to each episode and it’s opening episode was top of the polls once again over the holidays, a ratings-pull for the UK and US – an ongoing valuable import/export for the tv schedules.

The pitch of ‘Sherlock Holmes in the modern era‘ might have been fraught with danger (it had been tried before to varying success-rates largely ranging from stone-cold to tepid) but show-runners Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss had a track-record of projects full of clever dialogue and toying with audience preconceptions. This would be the sort of show that encouraged viewers to think and then to kick themselves for not spotting things sooner. It would delve deep into the existing world of Sherlock Holmes created by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and would take precise inspiration, not just ‘fast-food franchise’ the name alone. The modern Holmes might have to deal with social-media rather than deer-stalkers, but his weapon was still the mind, the ability to be one-step ahead of the viewer, but no so far ahead they couldn’t meet him at the finishing line. Its debut in 2010 was an immediate success – consolidating the creative team’s influence and boosting the careers of its already notable performers. Clever and stylish, it was the kind of show that everyone who was anyone would be talking about beside the ‘water-cooler’ the following day.

But if anyone watched the very first story (A Study in Pink, which aired in October 2010) and then time-jumped to the New Year’s Day 2017 chapter entitled The Six Thatchers (the first real episode in nearly three years) they would likely be scratching their heads at a show with the same wardrobe and faces but a very different strut. It wouldn’t be that the mythology was any more complicated – the cast has remained primarily the same – but that Sherlock‘s central remit is no longer to be a show about a prickly genius solving the crime through amazing but logical deductive reasoning. Bit by bit, that blueprint has changed, the barometer swinging to a show paying far more attention to snark and banter and less and less to the logic needed to tie things off in a satisfactory way. There’s lip-service given to mentions of how Holmes puts two and two together but it’s now essentially background noise to ‘performances’ that are just that: writers and actors knowing they can do this in their sleep. Fun though it can be, to call Sherlock a detective show is essentially the same logic as calling Blackadder a shoe-in for the History Channel. A little like The Avengers series of the 1960s or even The Prisoner of the same period, Sherlock is now a show driven by its star power and feeling less and less the need to reflect any real sense of logic. Had he been able to see them, Doyle might well have been a huge fan of early episodes, but by now he’d likely be bored or baffled.

A little like ‘The Avengers’ series of the 1960s or even ‘The Prisoner’ of the same period, ‘Sherlock’ is now a show driven by its star power… and feeling less and less the need to reflect any real sense of logic. Had he been able to see them, Doyle might well have been a huge fan of early episodes, but by now he’d likely be bored or baffled…

This New Year’s Day outing was a prime example of what the show does, for better and worse. In many previous installments there was at least the pretense of a story based slyly on an original Arthur Conan Doyle work, with a twist. But although The Six Thatchers gave passing nod in its title to The Adventure of the Six Napoleons, it was less of a story and more than a series of loosely-connected vignettes that were left scattered on the floor like discarded pieces of discarded paper beneath an ornate but clunky typewriter. Even the title – in this case a reference to six busts of the late UK Conservatives’ leader – was fairly tangential to eventual proceedings.

Cumberbatch continues to be the spokesperson for enigmatic detached characters as much as Freeman is for determined but weary everymen… and both actors are usually worth the price of admission. They are the Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, the Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, the Batman and Robin of the stage and screen. Gatiss once again eats scenery as he pulls double-duty as Mycroft, the kind of grotesquely comical bureaucrat who kicks kittens and probably wants to see Aladdin locked up in a cave each Christmas. Amanda Abbington as Mary Watson was the best fleshed out supporting character, a match for Sherlock emotionally but one whose mere presence emasculates her husband’s place in the opening 2017 story. Though not for long….

Yes, Mary Watson – a la the Doyle stories – was written out this year, by unspecified means in the original books but here by impossibly taking a bullet for Sherlock. It gives some weight to the opinion that she’s the latest example of ‘fridging‘ (where a female character is killed off merely to provide emotional angst for the heroes) though there’s an argument to be made against that description given that the original Mary was discarded a century before. However it did give Abbington (who’d known about the planned exit since joining the show) a powerful send-off, gave Freeman the opportunity for a truly gut-wrenching howl and our modern Sherlock convenient moments of apparent remorse and guilt (so not a total sociopath, then?)

The second episode of the new run, The Lying Detective, was more of the same, if an improvement of sorts… there’s an array of acting that ranges from the good (Cumberbatch, Freeman – of course – with Abbington surprisingly still a major presence) to an over-the-top Toby Jones. The nuanced character-actor misses a significant opportunity to get his teeth in to a character inspired by the very real monster that was Jimmy Savile but who plunged into ill-advised acidic pantomime territory far too quickly leaving it all feeling the wrong kind of unpleasant. Once again, the performances couldn’t hide a story that had all the right elements and huge potential but couldn’t mix them together without cramping their styles. (Though Una Stubbs, at last, steals the episode). A last minute revelation, admittedly nicely seeded through the stories so far, sets up a ‘big’ final episode, but feels tacked on like an epilogue afterthought.

That finale, The Final Problem (a spin on the Doyle case The Final Solution where – bored with Holmes – the author killed him off at least temporarily) will likely divide viewers even further. The revelation of a third Holmes sibling – all of them blessed or crippled with cognitive quirks and names that feel like bad hands at Scrabble – sees the show spin-off into territory that feels like a blend of key Batman stories The Killing Joke and The Dark Knight Returns, with sister Eurus (Sian Brooke) playing the best Joker / Riddler this side of Gotham City. Suddenly our beloved Holmes, Mycroft and Watson are surviving CGI’d explosions, journeying to an evil supervillain base that feels like Arkham-Asylum-by-the-sea, trying to stop a plane possibly diving into the heart of London and other things that feel far more James Bond than Sherlock Holmes.

That being said, however theatrical it all feels, Sian Brooke’s performance as Eurus is the stand-out here. Eagle-eyed viewers will have spotted in throughout the run (disguised as a psychiatrist and Watson’s ‘other woman’), but as the lost Holmes sister she’s given the leeway to give a performance that’s largely hinged (or unhinged) through tiny inflections of voice and physical movement of face and body and it’s no surprise that she and Cumberbtach have worked together before on stage. The story’s conceots may stretch suspension of disbelief but its her performance that keeps your eyes on the screen and away from logic-flaws as she ‘tests’ out ‘heroes’. It’s interesting how much effort the show has spent on making secondary female characters so influential but damning to our heroes. It’s not fridging, but it does have an element of ice to it.

(C) Hartswood Films – Photographer: Todd Antony

Moffat and Gatiss have always had a sense of style and subversion but they also appear to get bored easily. Cliffhangers are often elaborately set-up and then disposed of with a line of dialogue or never explained at all. (“I think people have come to think a plot hole is something which isn’t explained on screen,” Moffat told the Telegraph in 2014. “A plot hole is actually something that can’t be explained. Sometimes you expect the audience to put two and two together for themselves. For Sherlock, and indeed Dr Who, I’ve always made the assumption that the audience is clever.”)

True. But used TOO often or disdainfully it can also be a convenient get-out for lazy writing – because the audience aren’t paid to be the writers. Sherlock is a shiny, high-production series where you can enjoy absurd elements in the moment even if afterwards the whole thing falls part logically. THAT, in many ways, is the defining flaw of this version. Sherlock Holmes, by sheer definition, should be the exact opposite of the current set-up. It should be: ‘Oh that doesn’t seem to make a lick of sense but… wait…. oh, of course it does!‘.

Does the show have a future? The end of The Final Problem seems as much a goodbye as the end of a long origin story. The ratings and star-power involved would normally suggest its survival was more than secured. But there’s the pragmatic flipside of cast availability and the narrative problem of moving forward in a show that is continuously looking back at its rear-view-mirror source material while struggling to drive forward and in doing so tends to go around in circles.

To be fair though., while it’s relatively easy to point to specific shifts through the years, there’s also a danger in merely jumping on the populist bandwagon of criticism against a show that has found its niche. Moffat and Gatiss and their narrative ticks can be lightning-rods for strong opinions – just ask their Doctor Who fandom. The problems that arguably dog the Sherlock like a Baskerville hound may not actually be seen as failings at all by some of the audience. Those there for ninety-minutes of snarks, heightened reality, OTT characters and the sheer Cumbatchiness of it all will still find themselves well taken care of. Most episodes do have some memorable moments or lines that will make you smile. Holmes’ ability to be the obviously socially-awkward but technically intellectual superior to everyone he meets, is clearly a potent dramatic formula – one that has echoed down through pop-culture since it was first written. Modern equivalents, ranging from Gregory House to The Big Bang Theory‘s Sheldon Cooper, have provided much mirth and rolling of eyes as they try to tolerate tolerance and their ‘inferiors’. But such characters – and possibly writers – unbound by the need to explain or please, also have a shelf-life for that very reason.

If The Final Problem is the end of this particular tv version it’s a decent send-off to a certain signature style, one with homage as the sincerest form of flattery and snark the popular form of sincerity. But one suspects Arthur Conan Doyle himself could probably give Moffat and Gatiss the best advice: that, however tempting it might be, there’s a point you shouldn’t continue to chase waterfalls.

- Story7

- Acting8

- Pacing7

- Writing7

- Worth the wait?8