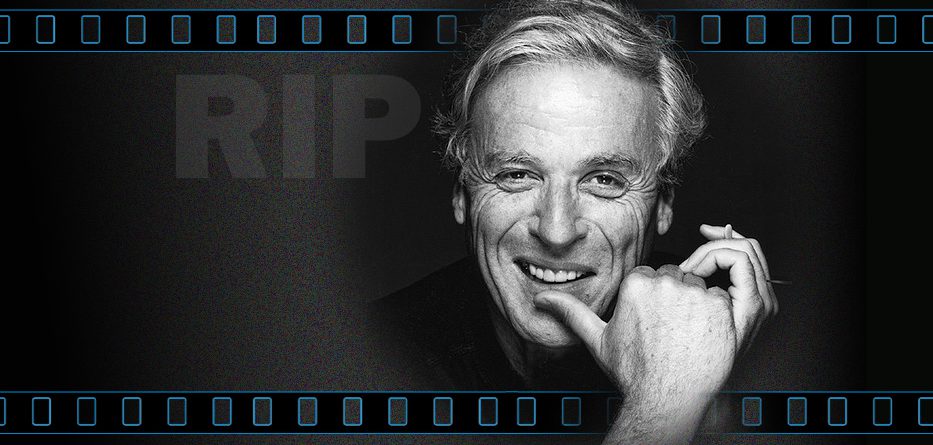

In a city and industry built on a foundation of a million maxims and intangible trends, there’s perhaps only absolutely one piece of definitive truth to offer. “Nobody knows anything..” said William Goldman, proving perhaps that one person, ironically, did.

Ask many veterans of the film-making world and almost every one will cite William Goldman as a cornerstone, touchstone and general sword in the stone that could be drawn out and used as a barometer against which to judge themselves. Already becoming a successful writer, he became known for penning Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (directed by George Roy Hill) which Goldman’s sold to 20th Century Fox for an apparent $400,000. It was a film that quickly caught the public imagination and despite the sniffiness of some critics went on to become one of 1969’s highest-grossing films, a beloved western and the winner of four Academy Awards, including Best Screenplay. For some that would have been the highlight and high point of their careers – but not Goldman. It was just the beginning. He worked on The Stepford Wives and The Great Waldo Pepper (both 1975) and with both Redford and Dustin Hoffman for the story of the Watergate cover-up in 1976’s All the President’s Men (directed by Alan Pakula and which, again, won the year’s Best Screenplay). Other classics for which he was credited for screenplay or writing included A Bridge Too Far (1977), Misery (1990) for which Kathy Bates won an Academy Award, Chaplin (1992) for which Robert Downry Jnr. received an Academy Award nomination, Maverick (1994), Absolute Power (1997) and Hearts in Atlantis (2001).

He adapted some of his own novels and ideas, most famously 1976’s thriller Marathon Man (which historically pitted Hoffman and Lawrence Olivier against each other on and off screen), 1978’s memorably spooky Magic (starring Anthony Hopkins and directed by Richard Attenborough) and – of course – 1987’s beloved subversive fairy-tale The Princess Bride (directed by Rob Reiner and with some of the most quoted movie lines in history).

He was often the go-to for others, offering some sage advice – officially or unofficially – to fellow film-makers if they asked. He contributed, though without formal credit, to 1973’s Papillon (directed by Franklin J. Schaffner and starring Steve McQueen and Dustin Hoffman) as well as Twins (1988), Rob Reiner’s A Few Good Men (1992), Adrian Lynne’s Indecent Proposal (1993) and Last Action hero (also 1993) . He suggested a different final-cut to 1991’s Silence of the Lambs (that director Jonathan Demme initially balked at but which he quickly agreed made the film far better) and apparently spent a day with the fledgling Ben Affleck and Matt Damon as the upcoming writer/actors began their rise with 1997’s Good Will Hunting (There remained a rumour that Goldman wrote the script for which Affleck and Damon collected the Academy Award, but he always denied any more than suggesting they cut out a specific extra story thread that wasn’t needed).

He was unafraid of speaking truth – or at least his opinion – unto power and would be happy to offer brickbats and bouquets as and when required. He once spoke of the fact that he’d read the script for Rocky and was disappointed that Stallone went on to become a movie ‘star’ rather than pursue the writing side. “God, read it, it’s wonderful. It’s just got marvelous stuff. And then he stopped suddenly because it’s easier being a movie star and making all that money than going in your pit and writing a script…” he mused. He also told The Guardian‘s Joe Queenan of his respect for Clint Eastwood… “Directors lose it around age 60. They’re either too rich or they can’t get work any more. And it’s physically debilitating work. That’s why Gran Torino amazes me. Clint Eastwood is 78 and he can still make a movie like that. He is having the most amazing career.”

His opinion of being a writer-for-hire in Hollywood over the years was brought in to sharp focus with Adventures in the Screen Trade, first published in 1983 and never out of print since. Even to this day, it is generally revered as one of the most brutally honest and accounts of the timeless miseries and joy of the profession and how fickle it can be. In 2000, he published a follow-up Which Lie Did I Tell?.

Inconceivably, William Goldman – or Simon Morgenstern to his friends and family from Florin – died 15th November aged 87, with his daughter confirming he had passed from complications of colon cancer and pneumonia.